1. Bottom line – the county court is the civil court most people deal with. Before issuing a claim, you must try to settle outside of court and send a letter before action; ignoring this step can weaken or even invalidate your case. Keeping a clear audit trail and using digital tools will help you avoid the administrative pitfalls that often shut out litigants in person.

2. Do first – consider whether the dispute can be resolved without proceedings. Claims of up to £10,000 are allocated to the Small Claims Track and are automatically referred to the Small Claims Mediation Service, with mandatory free mediation integrated into the court process from May 2024. Claims between £10,000 and £25,000 generally fall within the fast track, while larger fixed-sum claims may be issued via Money Claim Online.

3. Stay organised – follow the court’s pre-action protocols, keep copies of all filings and confirmations, and use the official Find a court service to identify the correct county court. After a judgment, enforcement is not automatic; you must request a warrant of control, an attachment of earnings order or other remedies.

If you’re dealing with the county court without a solicitor, the hardest part is often not the law; it’s the process. Many claims in the civil court are delayed or rejected because of missing documents, unclear forms, or missed steps, not because the case itself is weak.

This guide explains how the county court in the UK works, when settling outside of court makes sense, how to find a county court, and how to avoid the common administrative mistakes that cause people to get stuck in “court uk” limbo, with a practical, step-by-step approach for litigants in person.

What Does “Civil Court” Mean and Where Does the County Court Fit?

The UK’s civil courts deal with disputes between individuals and organisations, contract disagreements, unpaid debts, consumer rights issues and property problems. They are separate from criminal courts, which decide whether someone has broken criminal law. Civil courts include the High Court (for complex or high‑value claims) and the county court, which handles most claims.

Within the county court, there are three tracks designed to match the complexity and value of the case:

| Track | Value (guide) | Typical cases | Notes |

| Small‑claims track | Up to £10 000 | Faulty goods, refunds, deposit disputes, and minor landlord–tenant issues | Less formal hearings; legal costs are rarely recoverable. |

| Fast‑track | £10 000–25 000 | Larger consumer disputes, straightforward contract claims | Usually, a short trial (one day). |

Litigants in person (LiPs) should check which track is appropriate. If the value is over £100,000 or the case is especially complex, it may go to the High Court. Cases for personal injury and housing repair have lower limits. Court UK searches sometimes point people to general court pages; always double‑check you’re looking at a civil court, not a criminal one.

The court you use depends not only on value but also on jurisdiction. County courts in England and Wales are local; you generally file where the defendant lives or where the dispute arose. When in doubt, seek legal advice or use the official court finder (described below).

Before You Take It to Court: Settling Outside of Court

For litigants in person, this stage is often where otherwise valid claims fail, not because the case lacks merit, but because pre-action steps are missed, mis-sequenced, or poorly evidenced, triggering the “gatekeeper” effect described in recent court access research.

Comply with the Pre‑Action Protocols

Before filing a claim, the court expects both sides to follow pre‑action protocols. You must try to settle the dispute and send a letter before action that explains your case and gives the other party time to respond. Failing to comply with this guidance can damage or even invalidate your claim.

A good letter before action should:

- Summarise the facts and the legal basis of your claim.

- Set out what you want (for example, payment of £850 plus interest).

- Provide copies of evidence (invoices, correspondence, photos).

- Give a reasonable deadline (usually 14 days) for the other party to respond.

CaseCraft.AI’s letter before action generator helps you structure this letter and ensures you include all necessary information.

Explore Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

Mediation and other ADR methods can resolve disputes without going to court. GOV.UK notes that mediation is confidential, quicker and less expensive than court proceedings, and allows you to stay in control of the outcome. Mediators are impartial and help parties negotiate a mutually acceptable solution. You can mediate at any stage before the hearing, and some county courts offer a telephone mediation service for small claims.

Other ADR options include:

- Ombudsmen (e.g., financial services or property), which can make binding decisions.

- Industry schemes, such as the Furniture & Home Improvement Ombudsman.

- Arbitration is more formal than mediation, but still private.

If you reach a settlement, record it in a signed settlement agreement. For higher‑value disputes, it can be wise to seek independent legal advice on the settlement’s terms.

If ADR fails or the other party ignores your letter, you can proceed to file your claim.

How to Start a Claim in the County Court (Step by Step)

Starting a claim involves paperwork, fees and strict deadlines. Here is a simplified framework:

- Assess your claim: Decide whether you need the small‑claims, fast‑track or multi‑track. Consider whether the defendant has assets to pay. Remember, you generally have six years from the date of the breach to file a claim.

- Gather evidence: Organise documents, contracts, invoices, emails, and photos, and keep a timeline.

- Choose the right court and form: Complete form N1 (claim form). If you’re claiming around £10,000, you’ll likely be on the fast track.

- Pay the fee: Court fees depend on the claim value (e.g., 5% of the amount claimed for sums over £10,000). You may be eligible for fee remission (see Form EX160A).

- Serve the claim: Once issued, the claim form and particulars must be served on the defendant. The defendant has 14 days to acknowledge and a further 14 days to file a defence.

- Follow directions: If the defendant defends the claim, the court will send directions questionnaires asking about witnesses, expert evidence and availability. Failure to comply can lead to strike‑out or cost orders.

- Prepare for the hearing: Exchange witness statements and evidence bundles by the deadline. Bring three copies to the hearing, one for you, one for the defendant and one for the judge.

Each county court may have slightly different procedures. Keep notes of all communications (letters, phone calls) and log when documents were sent and received to avoid disputes about service.

How to Find a County Court (and Why “Where” Matters)?

Find a court or tribunal service on GOV.UK provides the practical information you need before attending a law court. For any given court or tribunal, it lists the address, contact details, opening times, areas of law covered and disabled access. You can filter by location or postcode and see a map.

Why is location important?

- Jurisdiction: Claims are generally issued in the defendant’s local county court. For property disputes, an issue in court is the property’s location.

- Convenience: Hearings are held in person unless a judge directs otherwise. Choosing a convenient court saves time and travel costs.

- Administrative centre: Some courts, like the County Court Business Centre and Civil National Business Centre, handle online claims and paperwork. You may never attend in person, but still need the correct centre.

Using the correct court from the start reduces delays and the risk of your claim being returned.

The hidden risk for litigants in person: administrative failure

Recent research by the community interest company Blind Justice found that complex court administrative processes can act as gatekeepers to justice. Despite digital modernisation, current systems mostly serve professional users. Unrepresented litigants rely on high‑volume call‑centre systems that provide inconsistent advice. Problems identified include:

- Documents not logged: Filings are lost or never placed before a judge.

- Conflicting guidance: Different court staff give contradictory instructions.

- Long call‑centre waits: LiPs spend over 20 cumulative hours on hold.

- No unified portal: There’s no central place to check the case file or confirm receipt of documents.

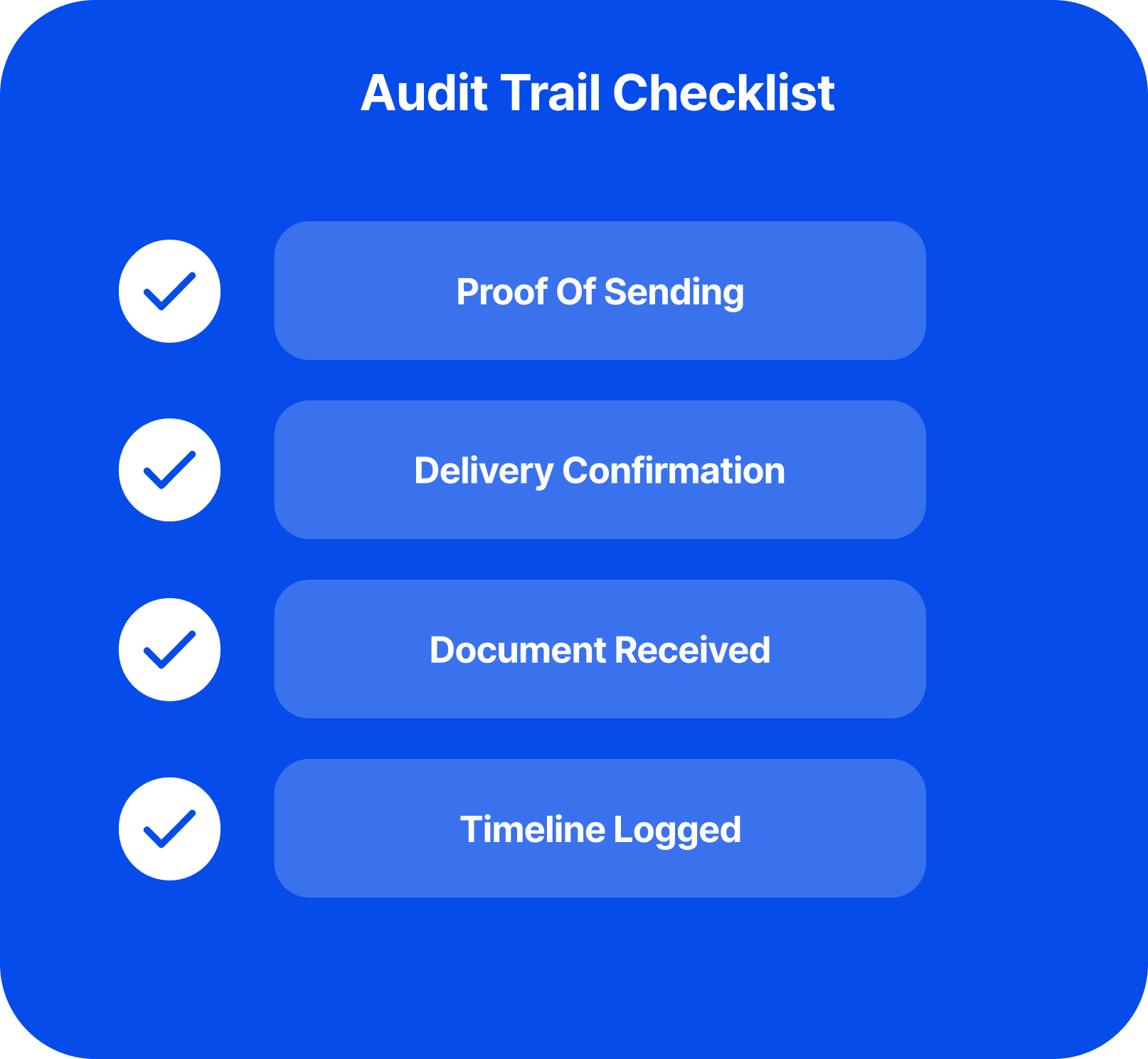

These failures cause missed deadlines and procedural prejudice. Without a lawyer, litigants have no effective mechanism to correct the record. To protect yourself:

- Keep an audit trail: Record when you sent documents, ask for proof of delivery and keep confirmations. CaseCraft.AI’s workflow automatically logs these milestones.

- Follow up in writing: After phone calls, send a brief email summarising what was discussed and ask for confirmation.

- Be proactive: If you don’t get a response within the specified time, chase the court or use recorded delivery.

By treating administration as part of your case strategy, you reduce the risk of being shut out by bureaucratic error.

After Judgment: Enforcement, Debt Resolution and Debt Collectors

Winning a case doesn’t guarantee payment. If the defendant doesn’t pay voluntarily, the court will not enforce the judgment unless you ask it to. You must choose an enforcement method and pay a further fee. The main options include:

| Enforcement method | Summary |

| Warrant of control | Authorises bailiffs to seize and sell the defendant’s goods to pay the judgment. Suitable for relatively small debts where the defendant owns assets. |

| Attachment of earnings order | Orders the defendant’s employer to deduct money from wages. Works only if the defendant is employed. |

| Third‑party debt order | Freezes money held in the defendant’s bank or building society account. |

| Charging order | Places a charge on the defendant’s property so that the debt is repaid when the property is sold. |

You can also apply to make the defendant bankrupt if they owe more than £5,000, but this is expensive and should be a last resort. Before choosing a method, consider whether the defendant has assets or income; the court will not refund your enforcement fee if you recover nothing.

If the defendant still refuses to pay, specialist debt‑collection agencies or High Court enforcement officers may be necessary. Always check the cost–benefit of each option and remember that enforcement can take time.

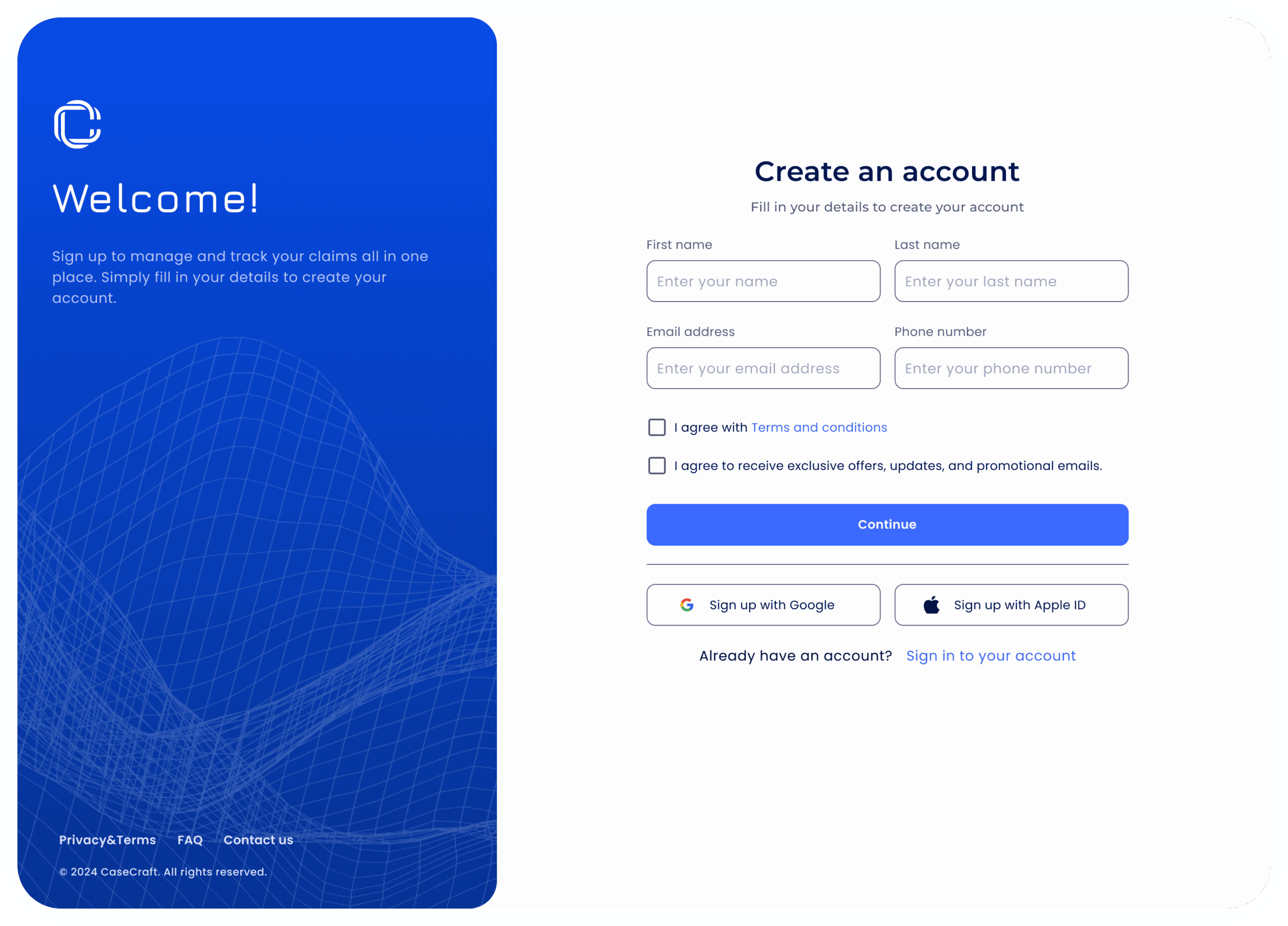

Why CaseCraft.AI?

CaseCraft.AI is designed for litigants in person who want to stay in control. Its workflow walks you through the pre‑action stages, helps you generate letters before action, organises evidence bundles, and reminds you of deadlines. The platform keeps a secure audit trail with proof of sending, delivery confirmations and a timeline so you can demonstrate compliance. Because Blind Justice’s research highlights administrative failures as a major barrier, having an organised digital workflow isn’t just convenient; it protects your rights.

Ready to take control of your dispute? Get started with CaseCraft.AI today.

FAQ

Do I need a lawyer to go to the county court?

No. The small‑claims track is designed to be accessible to people without lawyers. Court staff cannot give legal advice, so you are responsible for understanding the rules. Many litigants use guides like this or platforms such as CaseCraft.AI to organise their cases.

What happens if I don’t send a letter before action?

The court expects you to follow pre‑action protocols. If you file a claim without first attempting to settle, the judge may penalise you in costs or strike out your claim. Sending a well‑structured letter before action and allowing the defendant time to respond protects your position.

How long do county court proceedings take?

Timelines vary. A straightforward small‑claims case may settle or be decided at a hearing within a few months. A defended fast‑track case can take a year or more. Delays often arise from administrative backlog or missing documents. Keeping an organised timeline and following up with court staff helps keep your case moving.

How do I enforce a judgment?

You must apply for enforcement; the court won’t do it automatically. Options include a warrant of control, attachment of earnings order, third‑party debt order or charging order. Each carries a fee and may not guarantee success, so consider the defendant’s assets and seek advice if necessary.