1. Enforcement isn’t automatic – after winning a county court case, the judgment debtor has a short period to pay voluntarily; if they don’t, you must apply for enforcement.

2. Choose the right method – county court bailiffs (warrant of control), High Court enforcement (writ of control), attachment of earnings orders, charging orders and third‑party debt orders are all viable options; the choice depends on the debtor’s assets and employment status.

3. Expect separate forms and fees – each enforcement option requires a specific form (N323, N349, N379, N337 or N316) and attracts a court fee ranging from about £67 to £135

Introduction

Winning a County Court Judgment does not guarantee you will receive the money you are owed. Under the Civil Procedure Rules, a judgment debtor usually has 14 days to pay, but many ignore the order or pay late. If you let the judgment lapse without action, you risk losing the opportunity to recover your debt because most enforcement methods are subject to a six‑year limitation period. This article explains how to enforce a County Court Judgment (CCJ) through the UK small‑claims and county court system in 2025.

Imagine you won a small claim for £2,000 from a contractor who never finished the work. The court has ruled in your favour and issued a judgment. However, weeks go by, and the contractor still doesn’t pay. At this point, you need to shift from winning your case to enforcing it. That means applying for an enforcement order, such as a warrant of control, an attachment of earnings order or a charging order, and following statutory procedures to recover what is due. The process can be confusing, especially if you’re not familiar with legal forms or court fees

This guide walks you through each enforcement option step by step. We cover when to use county court bailiffs, when to transfer a judgment to the High Court, how to deduct money directly from wages, how to secure a debt against property, how to freeze bank accounts, how to obtain information about a debtor’s finances, how to add interest and costs, and when to get professional help

Understanding CCJ Enforcement in the UK

Before diving into individual enforcement methods, it helps to understand what a County Court Judgment is and why enforcement may be required. A CCJ is a court order stating that money is owed and specifying how it should be paid. It becomes enforceable once the judgment debtor fails to comply, whether by missing instalments or ignoring the order entirely. If the debtor doesn’t pay within the court’s deadline (usually 14 days), you must take active steps to enforce the judgment.

The Limitation Act 1980 imposes a six‑year time limit on enforcement actions. After six years, you cannot recover interest older than six years and must seek permission to enforce the judgment. Enforcement is a separate process from obtaining the judgment: you must submit the correct form and pay a fee for each method you choose. It is crucial to act promptly and keep accurate records of communications and payments. If you’re unsure about the small‑claims process, see our guide on what happens after you win a small claim.

Why Enforcement Matters

Enforcement is essential when a debtor ignores a court order. Unpaid judgments undermine the rule of law and can create cash‑flow problems for individuals and small businesses. The 2025 Civil Justice Council report highlighted delays and under‑funding in county court enforcement and recommended moving towards a unified digital court. Self‑represented claimants can still achieve successful outcomes by choosing the right enforcement method, documenting evidence of the debtor’s assets and acting quickly.

Step 1: Decide Which Enforcement Option Is Right for You

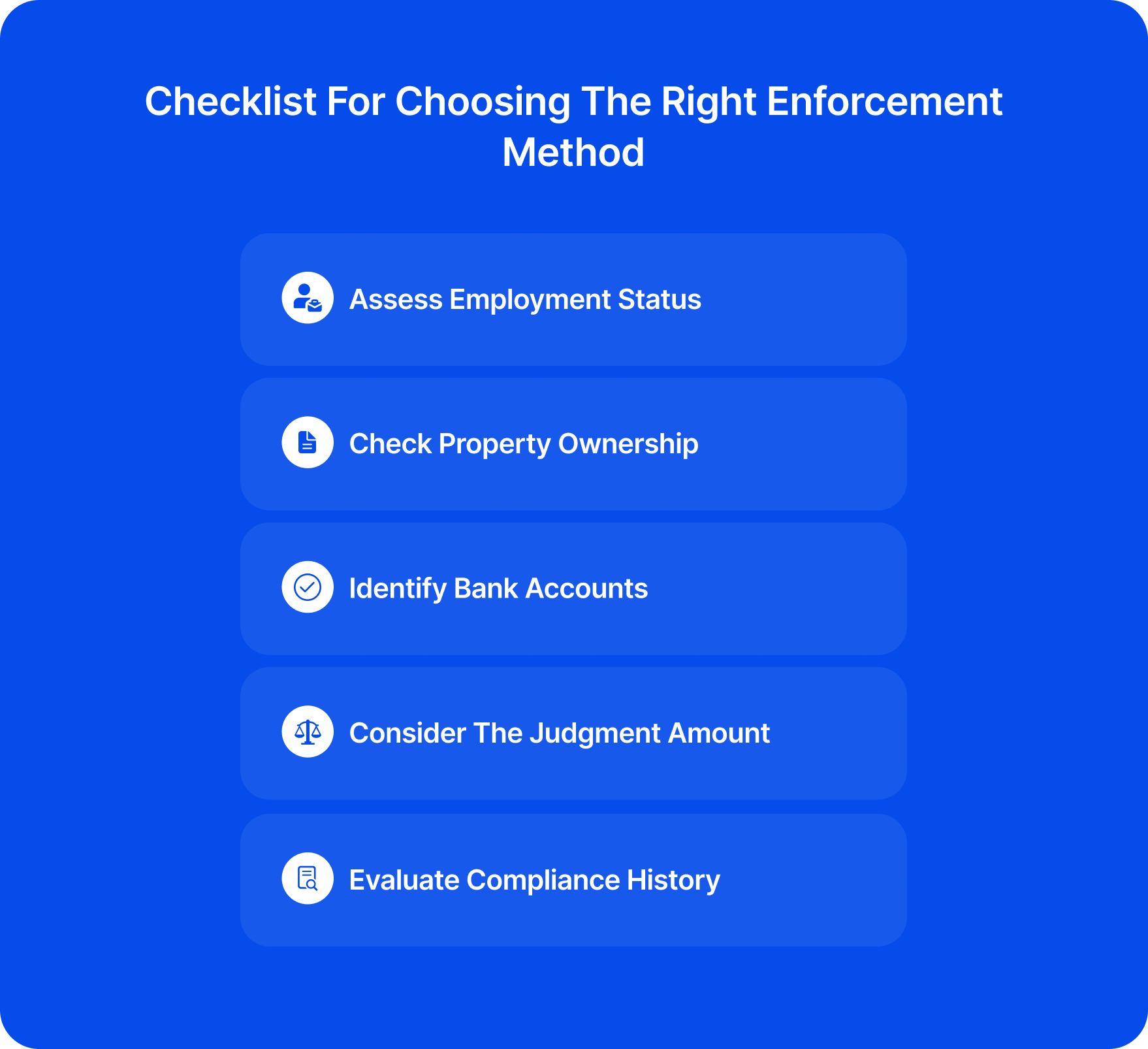

Selecting the correct enforcement method is the most important step. The best option depends on whether the judgment debtor is employed, self‑employed, owns property, holds funds in a bank account or has other assets. It also depends on the size of your claim and the debtor’s willingness to cooperate. A well‑documented understanding of the debtor’s circumstances increases the likelihood of recovery.

To make an informed decision:

- Assess employment status: Is the debtor employed by a company (not self‑employed or armed forces)? If so, an attachment of earnings order may be effective.

- Check property ownership: Does the debtor own a house, flat or land? A charging order can secure the debt against that property.

- Identify bank accounts: Do you know the debtor’s bank details? A third‑party debt order freezes funds held by a bank or other third party.

- Consider the judgment amount: Debts between £600 and £5,000 can be enforced by county court bailiffs; larger debts may benefit from transferring the judgment to the High Court.

- Evaluate compliance history: Has the debtor previously complied with court orders or ignored them? Persistent non‑payment may require stronger measures like High Court enforcement.

Once you know the debtor’s situation, proceed to the appropriate enforcement step below. Remember that you can pursue more than one method if initial attempts fail.

Step 2: Apply for a Warrant or Writ of Control

Judgment creditors often start with a warrant or writ of control because it allows enforcement officers to visit the debtor and collect payment or seize goods. There are two types: the county court warrant of control and the High Court writ of control. Both require an application fee and separate forms. Choose the method based on the amount of the judgment and the debtor’s asset profile.

Warrant of Control (County Court Bailiffs)

A warrant of control authorises county court bailiffs to attend the debtor’s address, demand payment, and, if necessary, seize and sell non‑essential goods to cover the debt and court enforcement fees. This method is suitable for judgments up to £5,000.

How It Works:

- Apply using form N323 – This form collects details about the creditor, debtor, and amount owed. You can file it in person or through an online portal (avoid using any competitor services). The current court fee is £94 according to the April 2025 fee schedule; this fee is added to the debt.

- Notice period and visit – The bailiff must give at least seven clear days’ notice before visiting the debtor. Visits can only occur between 6 am and 9 pm, and bailiffs must show identification and a copy of the warrant.

- What can be seized: Bailiffs may take non‑essential goods such as televisions, jewellery or vehicles. They cannot take clothing, bedding, basic household items or tools needed for work up to a value of £1,350.

- Outcome: If the debtor pays or goods are seized and sold, the proceeds are used to satisfy the judgment, the warrant fee and any bailiff costs. If the bailiff is unsuccessful (for example, if the debtor has no seizable assets), you can consider alternative enforcement methods.

Pros and cons: County court bailiffs have limited powers; they cannot force entry on a first visit, and their success depends on the debtor having valuable goods at the address. However, they are cost‑effective for small claims and can encourage payment through face‑to‑face engagement.

Writ of Control (High Court Enforcement Officer)

If your judgment is over £600 and not regulated by the Consumer Credit Act, you can transfer it to the High Court and issue a writ of control. High Court Enforcement Officers (HCEOs) have greater powers and can often act faster than county court bailiffs.

Procedure:

- Apply using form N293A – Complete the form and pay a transfer fee (about £80) plus enforcement costs. On approval, the High Court grants a writ of control.

- Interest and costs: Judgments enforced through the High Court accrue statutory interest at 8% per annum under the County Courts Act 1984. The enforcement costs are recoverable from the debtor if the officer collects payment.

- Execution: HCEOs can enter commercial premises using reasonable force and have broader authority to seize goods compared with county court bailiffs. They must still respect rules on exempt goods (essential household items and tools necessary for work).

- Outcome: HCEOs often achieve faster results but charge higher fees. If enforcement fails, you may lose the transfer fee, though the writ remains valid for one year.

When to use: A writ of control is beneficial for larger debts or where the debtor has valuable assets or operates a business. It may also be appropriate if the county court bailiff has been unsuccessful or if you wish to accrue interest.

Step 3: Attachment of Earnings Order

An attachment of earnings order is ideal when a judgment debtor is employed and has a steady income. It instructs their employer to deduct a portion of wages directly and send it to you until the debt is paid. This method is not suitable for self‑employed individuals or members of the armed forces and requires that at least £50 is owed.

How It Works

- Apply using form N337 – Provide details about the debtor, the judgment and the employer. If you are unsure whether the debtor is employed, you can obtain a search of the attachment‑of‑earnings index from the court.

- Court assessment: The court calculates a protected earnings rate to ensure the debtor retains enough income for essentials. The order is then served on the employer, who must deduct payments and forward them through the court’s Centralised Attachment of Earnings Payment System (CAPS).

- Fees: The application fee is around £135, and this cost is added to the judgment debt. Help with fees may be available if you receive benefits.

- Timeline: Expect 8–12 weeks from application to first payment. The debtor or employer can ask for a variation or suspension; ignoring the order can lead to penalties.

Pros and cons: Attachments of earnings provide a steady trickle of payments and ensure ongoing compliance. However, they are ineffective if the debtor changes jobs frequently, works for themselves or has a low income. Employers must not penalise employees because of the order, and the process is confidential.

Step 4: Charging Order (Secure Debt Against Property)

A charging order secures your judgment debt against the debtor’s home, land or other valuable assets. It does not require immediate payment but acts like a mortgage; when the property is sold, your debt must be settled. Charging orders are often used for larger debts or when the debtor has significant equity in property.

How to Apply

Apply for an interim order (Form N379) – The court will grant an interim order if you have a valid CCJ, even if instalments are up to date.

Notify the debtor and register the charge – Serve the order on the debtor and register it with HM Land Registry (for property) or the relevant asset register. This prevents the property from being sold without settling the debt.

Final order hearing – The court holds a hearing to decide whether to make the order final. The debtor may object. If granted, the charge remains until the debt is paid or the property is sold.

Optional order for sale – If the debtor still doesn’t pay, you can ask the court for an order for sale to force the property to be sold. Courts grant orders for sale sparingly and consider proportionality and family circumstances.

Fees: The application fee is around £135, plus Land Registry fees. These costs are added to the debt.

Pros and cons: Charging orders provide long‑term security and are useful when the debtor owns property, but they may delay payment. The debtor may refinance or voluntarily pay to remove the charge. However, if the property has little equity or multiple charges, your recovery may be limited.

Step 5: Third‑Party Debt Order

If you know the debtor has money in a bank or is owed funds by a third party, a third‑party debt order (TPDO) can freeze and transfer those funds to you. This method is useful when the debtor ignores other enforcement attempts and has accessible bank accounts or receivables.

How It Works

- Apply using form N349 – Provide details of the bank or third party holding the debtor’s funds. Pay the application fee of about £135.

- Interim order: The court issues an interim order that freezes the account or funds available on the day the order is served. The bank must identify accounts in the debtor’s name and suspend withdrawals. Timing matters – if the order is served before payday, there may be little money available.

- Final order hearing: A hearing is held where a judge decides whether to make the order final. Both parties can attend. If granted, the frozen funds (up to the judgment amount) are paid to you.

- Outcome: TPDOs are effective for one‑off payments but rely on accurate knowledge of the debtor’s bank details. The debtor can apply to vary or discharge the order if it causes hardship.

Pros and cons: Third‑party debt orders provide a direct way to recover funds without seizing goods or dealing with employers. However, you need precise banking information, and there is a risk that the account contains insufficient funds at the time of freezing.

Step 6: Order to Obtain Information

If you don’t know the debtor’s assets or financial situation, you can apply for an order to obtain information. This procedure compels the debtor to attend court and answer questions under oath about their income, property, bank accounts and other assets.

How to Apply and What to Expect

- Use form N316 or N316A – Form N316 is for individual debtors and N316A for companies. Specify the information you seek, such as employment details, dependants, property ownership or bank accounts.

- Service: Serve the order on the debtor at least 14 days before the scheduled hearing. The order warns that failure to attend or answer questions can lead to committal for contempt.

- Court questioning: During the interview, the debtor is placed under oath and asked about their financial situation. You may attend or send a representative to ask questions. A record is made and used to decide which enforcement method is appropriate.

- Consequences of non‑attendance: If the debtor doesn’t attend or refuses to answer, the court can issue a suspended committal order and eventually a warrant of arrest.

- Fees: The application fee is around £67 and is added to the debt.

Use cases: Orders to obtain information are valuable when you lack basic details about the debtor’s employment, property or bank accounts. They can also discourage evasive debtors, as failing to cooperate may result in arrest.

Step 7: Adding Interest and Costs

When enforcing a judgment in the UK, you may recover more than just the principal debt. Statutory interest and enforcement costs can often be added to the amount owed. Understanding when and how to add these amounts ensures you are fully compensated for the time and effort spent.

Adding Interest

Under the County Courts Act 1984, statutory interest of 8% per annum is payable when a judgment is enforced through the High Court. Not all county court judgments accrue interest automatically; check your judgment order for details. You can claim interest on the outstanding debt from the date of judgment until the date of payment. Interest cannot be recovered beyond six years.

Recovering Costs

You can add reasonable costs incurred during enforcement, including court fees and expenses, to the judgment debt. Below is a summary of which claim types attract statutory interest:

| Claim Type | Eligible for interest | Rate |

| Money judgment (High Court) | ✅ | 8% per year |

| Consumer Credit Act debt | ❌ | Not applicable |

Court fees for each enforcement method (April 2025):

- Warrant of control (N323) – £94

- Writ of control (N293A) – around £80 plus enforcement costs

- Attachment of earnings order (N337) – £135

- Charging order (N379) – £135

- Third‑party debt order (N349) – £135

- Order to obtain information (N316) – £67

These fees are generally recoverable from the debtor if enforcement succeeds

Source

Step 8: Enforcement Timeline and Expectations

Enforcement is rarely immediate. Depending on the chosen method and court workload, you may wait weeks or months before receiving payment. Being aware of typical timescales will help you manage expectations and plan accordingly.

Typical enforcement durations (based on 2025 guidance):

- Warrant of control: 6–10 weeks from application to resolution.

- Writ of control: 6–12 weeks, although HCEOs may act faster depending on the debtor’s assets.

- Attachment of earnings order: 8–12 weeks for the order to be processed and deductions to begin.

- Charging order: 10–16 weeks, including interim and final order hearings.

- Third‑party debt order: 8–14 weeks from application to final order.

Keep a detailed log of all correspondence, forms submitted and payments received. Follow up with the court if you hear nothing after the expected timeframe. If enforcement fails or you encounter unexpected delays, consider alternative methods or seek professional advice.

Step 9: When to Seek Professional Help

Most small claims can be enforced without legal representation, especially when using digital platforms designed for self‑represented claimants. However, complex or high‑value cases may require assistance from solicitors or enforcement agents. Consider professional help when:

- The debt exceeds £5,000 and involves multiple assets or high‑value goods.

- The debtor refuses to disclose assets, and you need thorough investigations.

- Cross‑border enforcement is necessary because the debtor lives or holds assets in Scotland, Northern Ireland or abroad.

- A case involves a company with complicated corporate structures.

Legal professionals can advise on the most effective enforcement method, handle applications and negotiate payment plans. They can also represent you at hearings, particularly when you seek orders for sale or deal with contested charging orders. Technology platforms like CaseCraft.AI can assist with preparing documentation, tracking deadlines and managing communication without replacing professional judgment.

Note: This article is for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. You should seek independent legal guidance or consult a qualified solicitor before taking any action related to court enforcement or small claims.

FAQ: Enforcing a County Court Judgment

How long do I have to enforce a County Court Judgment?

You generally have six years from the date the judgment became enforceable to start enforcement. After six years, you need the court’s permission, and you cannot claim an interest older than six years.

What is the difference between a warrant and a writ of control?

A warrant of control is issued by the county court for debts up to £5,000 and enforced by county court bailiffs. A writ of control is issued by the High Court after transferring the judgment and is enforced by High Court Enforcement Officers, who have broader powers and can add statutory interest.

Can I use bailiffs for any amount?

Bailiffs can enforce county court judgments up to £5,000. For debts over £600 (and unregulated by the Consumer Credit Act), you can transfer the judgment to the High Court and instruct a High Court Enforcement Officer.

How do I find out if the debtor owns property?

You can search the Land Registry to see if the debtor is the registered proprietor of a property. An order to obtain information (form N316) can also compel the debtor to disclose property ownership. Once confirmed, you may apply for a charging order to secure the debt.

Can I enforce a CCJ after six years?

Yes, but only with the court’s permission. The court will consider reasons for the delay and whether the debtor has suffered prejudice. You cannot recover interest that accrued more than six years ago.

What happens if the debtor goes bankrupt?

If the debtor becomes bankrupt, enforcement actions like bailiffs or attachment of earnings orders cease. Your debt may be unsecured in the bankruptcy process. You can still lodge a proof of debt with the trustee, but recovery depends on available assets and priority rules. Consider seeking legal advice if bankruptcy is imminent.